Since 1404, The Voynich Manuscript has floated between private collections, libraries, and continents. It has been owned by monks, alchemists and emperors. To this day, the meaning of its 170,00 words is a total mystery. This is that manuscript’s story. For more investigations beyond the threshold of human understanding, consider subscribing to EXO.

THE RARE BOOKSELLER

At 11pm on a warm June night in 1884, a chemistry student named Michał Habdank-Wojnicz crept through the dark streets of Warsaw clutching a bag filled with metalworking tools. His destination was the dreaded X Pavilion prison grounds in the city center where his revolutionary comrades of the First Proletariat were being held on death row by Russian imperial forces. His objective was to get the tools in the hands of his comrades so that they might saw through the bars of their jail cell. The plan was to help the comrades over the X Pavilion walls with a rope ladder, then hustle them out of the country. Things didn’t go according to plan.

A secret agent of the gendarme had infiltrated the ranks of the First Proletariat and thwarted the operation. The prisoners were hanged and Wojnicz was cast into penal servitude in the frozen climes of Siberia. Accounts of Wojnicz during this period are sparse, but fellow prisoners described his extraordinary ability to learn 18 languages in just two years. Wojnicz eventually escaped Siberia and traveled west by train to Hamburg. On October 13th, 1890 he made it to London.

In 1897, under the assumed named of Wilfrid Michael Voynich, he opened a bookshop at Soho Square. The newly named and situated Voynich displayed an uncanny gift for sourcing and acquiring hard-to-find books. One of his first scores was The Malermi Bible, the rarest translation of the holy scripture. At its high-water mark, his collection of manuscripts from the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries was valued at over half a million dollars, roughly equivalent to $19 million today.

Voynich’s most prized manuscripts were written in ciphers - code that had to be cracked to be understood. At one point he was identified as a possible enemy agent by the FBI, owing to his access to Bacon's Cipher, a method of message encoding considered to be a national threat to the US.

In 1902, Voynich acquired 30 manuscripts from The Roman College in Italy. Among the score was a manuscript containing text and illustrations so unusual, they might as well have been composed in a different galaxy.

Over the next century, thousands of linguists, paleographers, mathematicians, code breakers, botanists, historians, and computer scientists would race to identify the book’s author and understand its meaning.

To this day, The Voynich Manuscript remains an enigma.

Inside the Codex

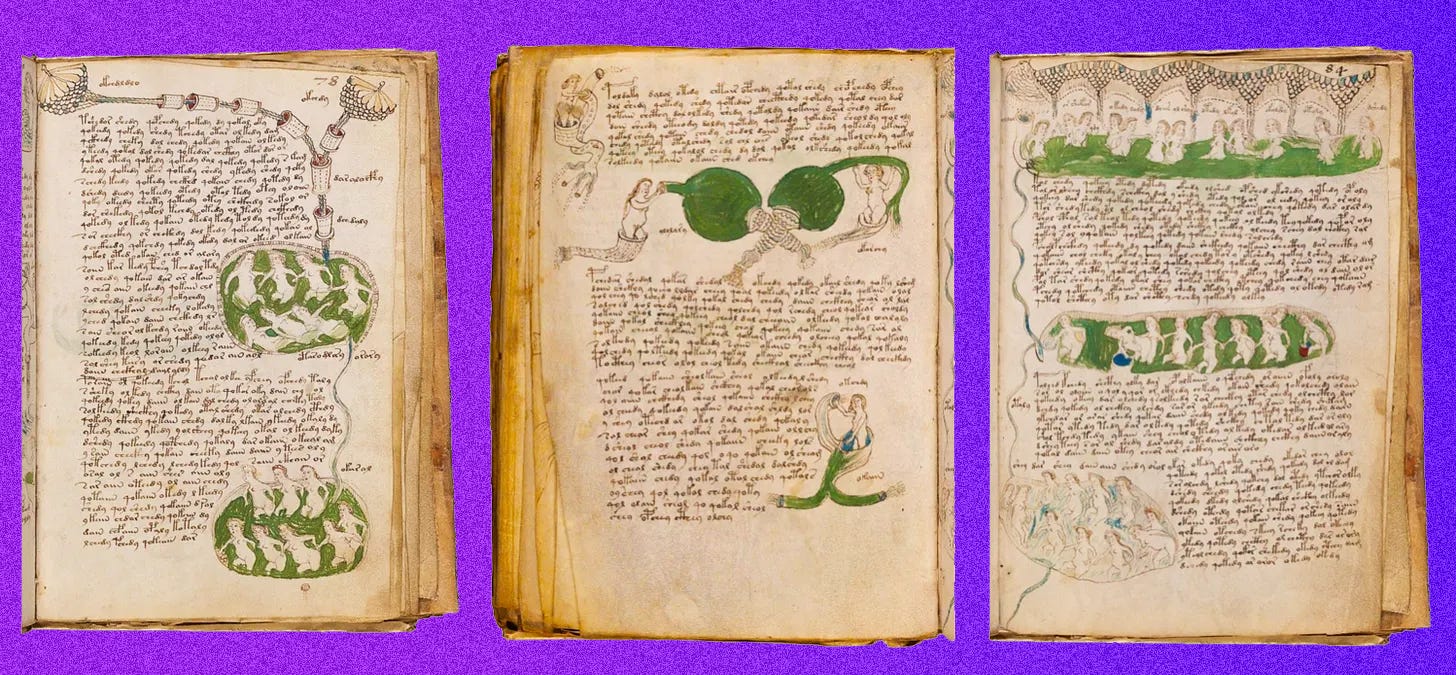

From 1969 up until present day, the Voynich Manuscript has lived in a dark vault at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Its 9 x 6-inch covers are made of goatskin, the result of refurbishing in the late-19th century. Insect holes in the back and front of the manuscript give away its original wood covers.

The manuscript once contained 272 pages, but only 240 have survived the test of time. The book’s contents are separated into six discrete sections.

The herbal section features paragraphs of mysterious text and 133 illustrations of exotic plant species.

The astronomical section features astrology diagrams. In one chart, 30 female figures are arranged in concentric bands. The women are at least partially nude, and each holds a star.

The nudity continues in the ‘Balneological’ section. For the unfamiliar, balneology is the medieval science of medicinal bathing. Each page is festooned with nude women. They lounge in pools connected by an elaborate network of pipes that resemble a fallopian tube-themed waterpark filled with green slime.

The cosmological section contains a maze of circular diagrams. One of the most elaborate sections is the ‘nine rosettes’, a 6-page foldout map of nine islands connected by bridges to castles and a volcano.

The last last three sections - Cosmological, Pharmaceutical and Recipes - only pull you deeper into the manuscript’s murky depths.

INTO THE UNKNOWN

The Voynich Manuscript is a never-ending labyrinth of tunnels that all lead to the same place: absolutely nowhere. Hundreds of technical essays, scientific analyses, and impassioned web forums have yielded precious little. Leafing through the pages is a journey through a glyphscape that is at once familiar and unnervingly foreign. Meaning flickers in the peripheral then disappears when examined head on…

The botanical section features what at first glance appear to be earthbound plants. However, all but two of the plants correspond with classified species in our botanical lexicon today. Peer closer, and the garden gets stranger. Some of the plants appear to be different species grafted together. In one section, the plants contain roots made of animal parts.

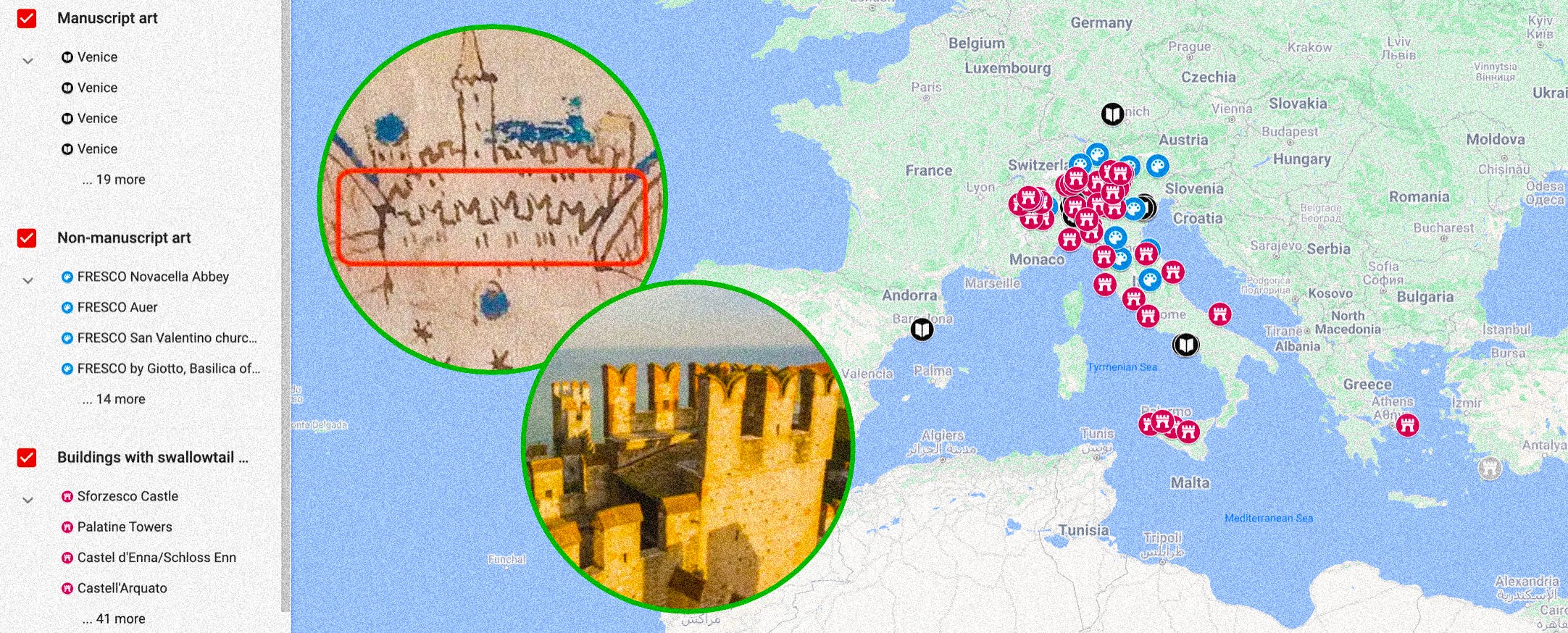

If you happen to be a student of medieval architecture and own a magnifying glass, you might notice the presence of swallowtail merlons atop the walls of a fortress depicted in the nine rosettes foldout. These distinct parapets might then point you towards the location of the book’s author. One enterprising researcher chased this minuscule detail down to the ends of the world, mapping the location of every IRL swallowtail merlon in the history of art and all still-standing castles. While the data clusters around Italy, it’s too spread out to draw anything close to a conclusion.

Yet another Voynich curveball is the style of text. The handwriting is sometimes flowing, sometimes cramped. This variation suggest there were five scribes. If the Voynich was a team effort, a deeper idiosyncrasy emerges. A mere two percent of the script contains corrections - meaningfully less than other 15th century works. One theory suggests the scribes had no idea what the text said, and therefore couldn’t notice spelling errors. Here again, a step toward understanding the manuscript’s production process, takes us one step away from the identity of the author.

The Voynich Manuscript’s mercurial imagery and text stylings lead us down one clue-less cul-de-sac after another. As a result, most efforts to get ahold of the keys to the manuscript’s meaning focus on the language itself. Welcome to the main event!

TEXTUAL ORIENTATION

In September of last year, leading Voynich scholar Lisa Fagin Davis was reviewing multispectral imaging on the first page of the manuscript when she spotted a column of Roman letters alongside a column of glyphs. The handwriting belonged to Johannes Marcus Marci, a doctor in Prague who owned the Voynich Manuscript from 1662 - 1665. Davis had just discovered the first attempt to decode a language that has become known as Voynichese.

Marci’s marginalia kicked off 400 years of attempted translations. While by no means a comprehensive list, here are some standout efforts.

In 1919, William Romaine Newbold, a professor of moral philosophy, published a book claiming that the Voynich text was double-wrapped in both a cipher and a far more sophisticated form of obfuscation he dubbed “anagrammed micrographic shorthand.’” Newbold described swarms of microscopic shorthand symbols hidden in individual pen strokes, that contained the clues to translation. Within ten years Newbold’s fabulous theory would be subjected to savage takedowns from the academic community and ultimately dismantled entirely.

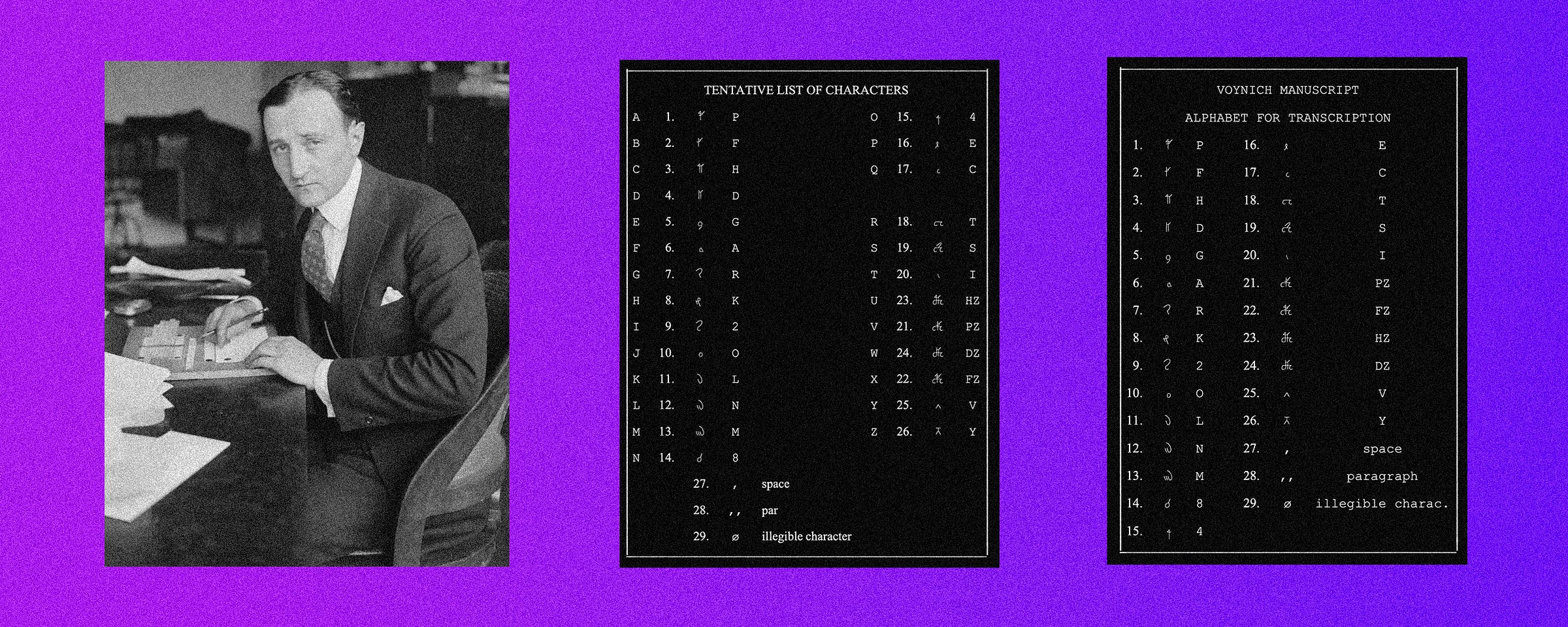

The baton then passed to former chief cryptanalyst for the US War Department William F Friedman. The challenge of deciphering the text would consume him for four decades. Friedman formed a club of Army cryptanalysts to tackle the project. The group spent its evenings assigning Voynich glyphs to English letters that were then transcoded on to IBM punchcards to make the language machine readable.

Towards the end of the 1950s, and his own life, Friedman took to the Philogical Quarterly to declare the Voynich a cryptological clusterfuck. He explained that there are two types of ciphers. Substitution ciphers replace letters with other letters according to a key known only to the parties attempting to communicate covertly. The more sophisticated transpositions cipher jumbles the letters of an original text. Only a key can put the letters back in the right order. The Voynich, he lamented, was a keyless transposition cipher that would doom any decoder forevermore. In the essay’s footnotes, Friedman wrote:

I PUT NO TRUST IN ANAGRAMMATIC ACROSTIC CYPHERS, FOR THEY ARE OF LITTLE REAL VALUE —A WASTE— AND MAY PROVE NOTHING. — FINIS.

This was itself an anagram that translated to:

THE VOYNICH MSS WAS AN EARLY ATTEMPT TO CONSTRUCT AN ARTIFICIAL OR UNIVERSAL LANGUAGE OF THE A PRIORI TYPE — FRIEDMAN.

Friedman had concluded that the author of the Voynich Manuscript invented the language, assuring any attempt at translation would result in gibberish. Indeed, not knowing the base language frustrated a wave of subsequent translation attempts since.

Friedman’s pessimistic conclusion dredged up an existential question that has haunted Voynich sleuths for decades: is there a language underneath the code at all?

MORPHEME OVERDRIVE

In 2004, writers Gerry Kennedy and Rob Churchill developed a theory that Voynichese could be glossolalia - a semi-intelligible stream-of-consciousness only understood by the speaker. A familiar example of glossolalia is the Pentecostal Christian preacher possessed by the spirit. Kennedy and Churchill went so far as to suggest that the original author might have suffered from severe migraines or a neurological disorder that induced a trancelike state; cue swirling incantations.

Thanks to the work of a team out of the University of São Paulo there is wide consensus today that Voynichese is indeed a full-fledged language. In 2013, the São Paulo team established a comparability framework to ascertain whether the manuscript is more akin to random text or a living breathing language. They focused on the script’s word frequencies and intertextual networks. One procedure analyzed the connectivity between small linguistic building blocks. The resulting ‘motifs’ display the lively interconnectivity of Voynichese. According to the team’s research, 90% of the text behaves like a natural language.

If the Voynich Manuscript isn’t enciphered random text, then what language is it? Almost monthly, students of the script pop up claiming to have identified the dialect that lies beneath.

In 2018, Stephan Vonfelt published The Strange Resonances of the Voynich Manuscript which rehashed previous research suggesting that Voynichese has the most in common with Chinese languages. Vonfelt focused on resonance, which measures the rhythmical cadence of a language like repetitive letter and word combinations. The resulting “memory persistence” indicates a linguistic circularity much closer to Chinese than European languages.

In 2019, researcher Gerard Cheshire published a paper declaring Voynichese to be a medieval ancestor of Romance languages like Portuguese, Spanish, French, Italian, Romanian, Catalan and Galician spoken in and around the Mediterranean. The theory was widely rejected.

In 2020, Greg Kondrak of the University of Alberta's renowned artificial intelligence lab published a computational analysis of the Voynich Manuscript that sported a new method for identifying a base language in cipher text. Kondrak developed an algorithm that compares the pattern distribution of characters in an unknown language with samples from human languages with 97% accuracy. His algorithm compared Voynichese with 380 different modern languages. To the surprise of scholars across the world, the findings indicated that statistically Voynichese had the most in common with Hebrew.

Detractors piled in on Kondrak immediately. Kondrak’s 380 sample languages were all modern, while the Voynich Manuscript was written in the early-15th century. Secondly, the 380 samples fail to encompass every known language. Without including all human languages in the comparative set, rating Hebrew gets us just about halfway to nowhere.

Kondrak’s team also built a decoder to re-arrange the letters if indeed the author had jumbled the text with an anagram cipher. Powerful as it was, this decoding layer provided unacceptable latitude for translation. Professor Shlomo Argamon, a computational linguist at Illinois Institute of Technology, dismissed Kondrak’s effort as an “impressionistic interpretation.”

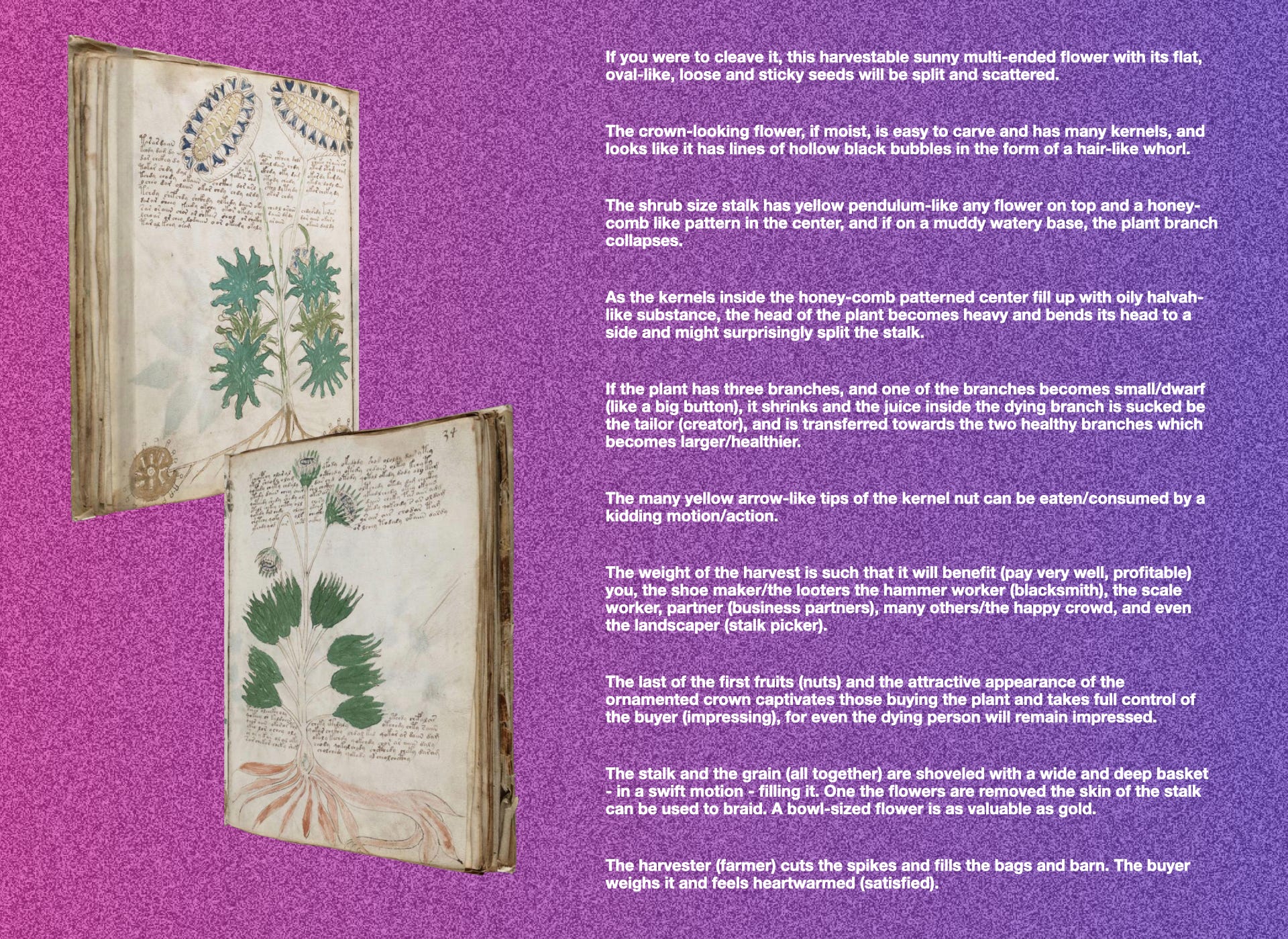

Perhaps the most compelling attempt at translating the Voynich Manuscript has come from a father-son duo out of Calgary. When electrical engineer Ahmet Ardıç was introduced to the Voynich Manuscript, he instantly recognized parallels with his native Turkish and specifically Old Turkic, which was spoken around East Turkistan and Mongolia from the 11th - 15th centuries. He enlisted his two sons to help him tackle the mystery as a “family project.” They called their crew Ata Team Alberta (ATA).

ATA mounted its case on the back of the Turkish language’s agglutinative structure, in which words are formed by stringing parts of other words together. ATA classifed Voynichese as phonemic orthography, a writing system in which letters and symbols are spelled the way they sound. By cross-referencing Voynichese and Old Turkic alphabets, then layering on creative translations, symbols and sounds, ATA claims to have successfully found the meaning of 300 words and 30% of the total script. Here’s an example:

In the above, Ahmet’s son Ozan identified an “I” and an inverse “P” in the loopy first character above. “IP” in Turkish means rope. Ozan suggests that the word is styled intentionally to also resemble a rope. His character-by-character comparison with Old Turkic translates the proceeding word to “measurement.” The full translation comes out to “rope measurement.”

Once ATA translated a meaningful batch of words, they tested their model on a single page of the manuscript, hoping to find parallels with the accompanying imagery. They took aim at Folio 33-V, in which the script commingles with freaky-looking flowers. This is ATA’s translation:

At first blush, you gotta hand it to ATA for the sheer specificity of their transcription. Thematically, it’s on point. The output even refers to a flower bending from the weight of the substance it carries until it “split[s] the stalk,” which is indeed depicted in the imagery. And yet, ATA’s theory has landed with a thud.

As with Kondrak, ATA’s inventive methodology leaves significant room for interpretation. The battle unfolds on the Voynich Ninja forum, where Ahmet Ardıç’s theory has run up against 67 pages of dissension. One user decries Ardıç’s generous “degrees of freedom.” The user points out that by assigning 7+ sounds per glyph and translating into multiple base dialects, ATA has given itself license to draw subjective meaning out of thin air. The online conversation has turned toxic, with users denouncing Ardıç’s “politically motivated fringe theory.” At the moment, Ardıç is “30% banned” from the forum, presumably in reference to his contentious claim that he’s transcribed 30% of the manuscript.

One can’t help but notice the ferocity with which the Voynich community rejects each and every new breakthrough. It reminds me of the similarly cryptographically-obsessed Bitcoin community and its outright indignation any time anyone tries to identify the pseudonymous founder Satoshi Nakamoto. It is as if the mysteries of the Voynich Manuscript hold the promise of realms beyond our understanding, and that we prefer it that way. Perhaps we are here to search not to find.

To continue the search, you can dive into the Voynich Manuscript here. Artificial Intelligence, I’m looking in your direction.

I was happy to know that a group from São Paulo, my hometown in Brazil, has a role in the story. And even happier to read something new from you! Great work!