Stanford Professor Garry Nolan Is Analyzing Anomalous Materials From UFO Crashes

A Q&A with one of the foremost scientists studying UAPs, and what he hopes to learn by systematically studying bizarre and difficult-to-explain incidents

EXO is expanding into a web3-powered publishing organization. If you‘re into raising the bar on how we tell stories on the Internet, tuning into out-there speakers, or simply enjoy a good old-fashioned digital soundbath, come on in.

OK, on with the show!

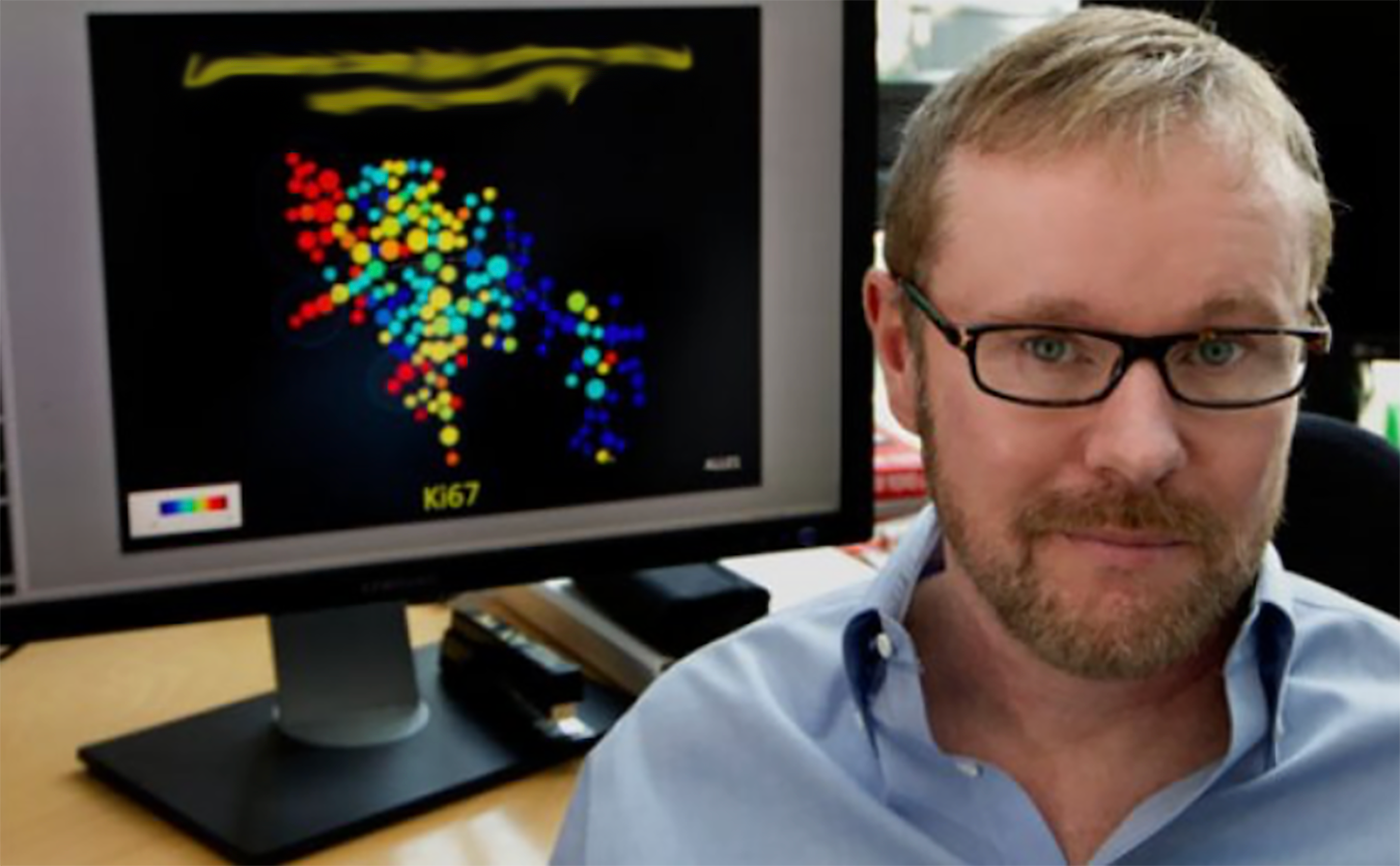

Dr. Garry Nolan is a Professor of Pathology at Stanford University. His research ranges from cancer to systems immunology. Dr. Nolan has also spent the last ten years working with a number of individual analyzing materials from alleged Unidentified Aerial Phenomenon.

His robust resume—300 research articles, 40 US patents, founding of eight biotech companies, and honored as one of Stanford’s top 25 inventors—makes him, easily, one of the most accomplished scientists publicly studying UAPs.

I sat down with Garry to discuss his work.

How long have you had an interest in UAPs?

I’ve always been an avid reader of science fiction, so it was natural at some point that when YouTube videos about UFOs began to make the rounds I might watch a few. I noticed that this guy at the time, Steven Greer, had claimed that a little skeleton might be an alien. I remember thinking, 'Oh, I can prove or disprove that.' And so I reached out to him. I eventually showed that it wasn't an alien, it was human. We explain a fair amount about why it looked the way it did. It had a number of mutations in skeletal genes that could potentially explain the biology. The UFO community didn't like me saying that. But you know, the truth is in the science. So, I had no problem just stating the facts. We published a paper and it ended up going worldwide. It was on the front page of just about every major newspaper. What's more appealing or clickbait than ‘Stanford professor sequences alien baby’?

That ended up bringing me to the attention of some people associated with the CIA and some aeronautics corporations. At the time, they had been investigating a number of cases of pilots who'd gotten close to supposed UAPs and the fields generated by them, as was claimed by the people who showed up at my office unannounced one day. There was enough drama around the Atacama skeleton that I had basically decided to forswear all continued involvement in this area. Then these guys showed up and said, ‘We need you to help us with this because we want to do blood analysis and everybody says that you've got the best blood analysis instrumentation on the planet.’ Then they started showing the MRIs of some of these pilots and ground personnel and intelligence agents who had been damaged. The MRIs were clear. You didn't even have to be an MD to see that there was a problem. Some of their brains were horribly, horribly damaged. And so that's what kind of got me involved.

Does the Department of Pathology at Stanford have a track record of pulling practical jokes on you?

I thought it was a practical joke at the beginning. But no, nobody was pulling a practical joke. And just as an aside, the school is completely supportive, and always has been of the work that I've been doing. When the Atacama thing hit the fan, they stepped in and helped me deal with the public relations issues around it.

Are you able to mention which folks from which governmental departments other than aeronautics approached you?

No, I'm not.

Can you describe the more anomalous effects on the brains you observed with the MRIs?

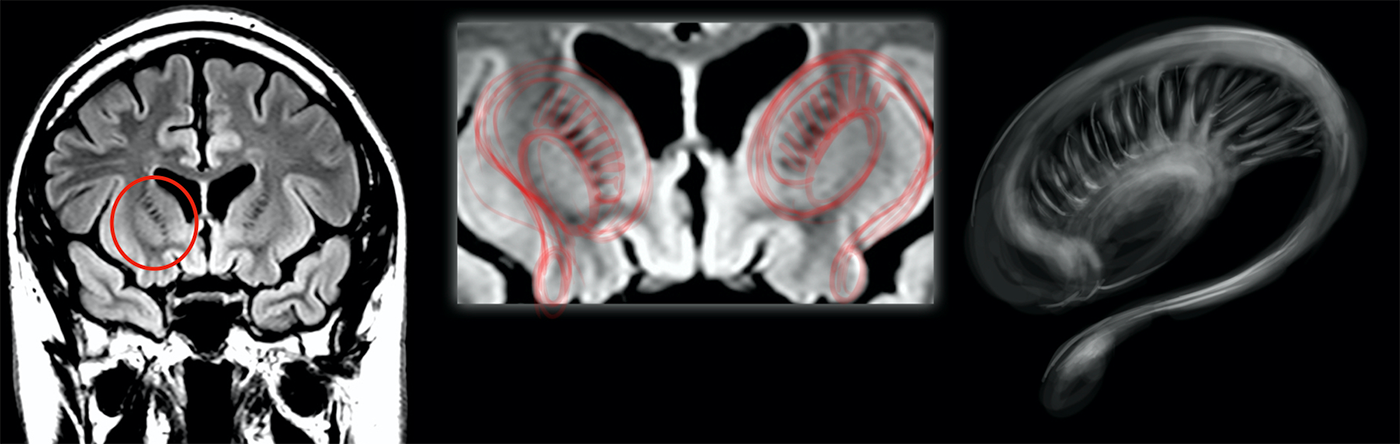

If you've ever looked at an MRI of somebody with multiple sclerosis, there's something called white matter disease. It's scarring. It's a big white blob, or multiple white blobs, scattered throughout the MRI. It's essentially dead tissue where the immune system has attacked the brain. That's probably the closest thing that you could come to if you wanted to look at a snapshot from one of these individuals. You can pretty quickly see that there's something wrong.

How many patients did you take a look at in that first phase?

It was around 100 patients. They were almost all defense or governmental personnel or people working in the aerospace industry; people doing government-level work. Here's how it works: Let's say that a Department of Defense personnel gets damaged or hurt. Odd cases go up the chain of command, at least within the medical branch. If nobody knows what to do with it, it goes over to what's called the weird desk, where things get thrown in a bucket. Then somebody eventually says, ‘Oh, there's enough interesting things in this bucket worth following up on that all look reasonably similar.’ Science works by comparing things that are similar and dissimilar to other things. Enough people were having very similar kinds of bad things happen to them, that it came to the attention of a guy by the name of Dr. Kit Green. He was in charge of studying some of these individuals. You have a smorgasbord of patients, some of whom had heard weird noises buzzing in their head, got sick, etc. A reasonable subset of them had claimed to have seen UAPs and some claimed to be close to things that got them sick. Let me show you the MRIs of the brains of some of these people.

We started to notice that there were similarities in what we thought was the damage across multiple individuals. As we looked more closely, though, we realized, well, that can't be damaged, because that's right in the middle of the basal ganglia [a group of nuclei responsible for motor control and other core brain functions]. If those structures were severely damaged, these people would be dead. That was when we realized that these people were not damaged, but had an over-connection of neurons between the head of the caudate and the putamen [The caudate nucleus plays a critical role in various higher neurological functions; the putamen influences motor planning, learning, and execution]. If you looked at 100 average people, you wouldn’t see this kind of density. But these individuals had it. An open question is: did coming in contact with whatever it was cause it or not?

For a couple of these individuals we had MRIs from prior years. They had it before they had these incidents. It was pretty obvious, then, that this was something that people were born with. It's a goal sub-goal setting planning device, it's called the brain within the brain. It's an extraordinary thing. This area of the brain is involved (partly) in what we call intuition. For instance, Japanese chess players were measured as they made what would be construed as a brilliant decision that is not obvious for anybody to have made that kind of leap of intuition, this area of the brain lights up. We had found people who had this in spades. These are all so called high-functioning people. They're pilots who are making split second decisions, intelligence officers in the field, etc.

Everybody has this connectivity region in general, but let’s say for the average person that the density level is 1x. Most of the people in the study had 5x to 10x and up to 15x, the normal density in this region. In this case we are speculating that density implies some sort of neuronal function.

Did the people who claimed that they'd had an encounter, especially the pilots, describe any perceivable decrease in neurological capacity?

Of the 100 or so patients that we looked at, about a quarter of them died from their injuries. The majority of these patients had symptomology that's basically identical to what's now called Havana syndrome. We think amongst this bucket list of cases, we had the first Havana syndrome patients. Once this turned into a national security problem with the Havana syndrome I was locked out of all of the access to the files because it's now a serious potential international incident if they ever figured out who's been doing it.

That still left individuals who had seen UAPs. They didn't have Havana syndrome. They had a smorgasbord of other symptoms.

How does the impact of electromagnetic frequencies factor into your hypotheses about what exactly transpired here?

With one of the patients, it happened on the Skinwalker Ranch. Given how deep into their brain the damage went, we can actually estimate the amount of energy required in the electromagnetic wave someone aimed at them. We don't think that has anything to do with UAPs. We think that that's some sort of a state actor and again related to Havana syndrome somehow.

Other than MRIs, what technologies were you using to analyze the patients?

We did a deep psychological evaluation of all of these people, just to make sure that they were stable and we were not dealing with obviously delusional individuals. My role in the initial project was analysis on blood, using a device called CyTOF which was something that I had been involved in the development of. The problem was that we couldn't really conclude very much because many of the cases happened years before I ended up getting the blood. With an acute injury to be seen in some telltale signature, we need to collect the within four or five days or a couple of weeks, but blood from an individual a couple of years out will not be useful. What I told the people in the government is I need access to their blood while the case is still acute.

Is there anything man-made that might have this impact on the brain?

The only thing I can imagine is you're standing next to an electric transformer that's emitting so much energy that you're basically getting burned inside your body.

Are you simply attempting to document what you see? Or are you looking for a cause as well?

Yes, it's kind of the natural way that science is done. First, you catalog, then you organize and then you say: well, this is similar to that and this other thing is similar to that but why is this other thing different? And then, if you have enough data, you start to look for causes. I do that every day with our cancer work. We always try to come up with hypotheses on why something is. Hypotheses are innumerable—they are proof of nothing. So, I am careful NOT to come to a premature conclusion because you only need one disproof to undermine a hypothesis. That's what I'm trying to stay away from. I have my private thoughts about what I think is going on, and some of them I'm very, very sure about. I'm open to being wrong. Except most of the time, I know I'm probably right.

You've also analyzed inanimate materials like alleged UAP fragments...

You've probably heard of Jacques Vallée, Kit Green, Eric Davis and Colm Kelleher. All roads lead to them when it comes to UAP. I basically became friends with that whole group; they call it The Invisible College. When they found out some of the instruments that I had developed, using mass spectrometry, they asked if I could analyze UAP material, and tell them something about it. That led to the development of a roadmap of how to analyze these things.

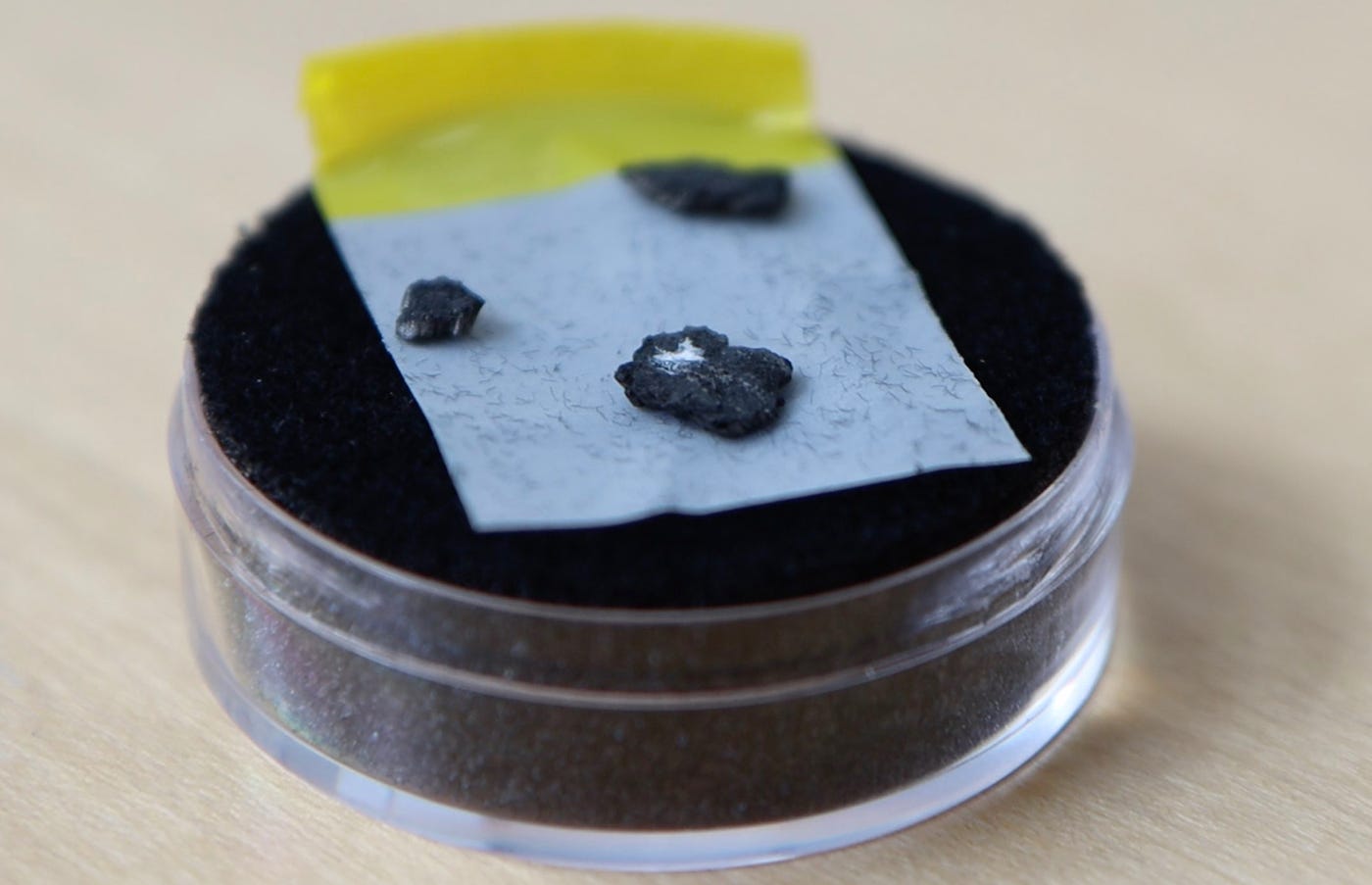

Some of the objects are nondescript, and just lumps of metal. Mostly, there's nothing unusual about them except that everywhere you look in the metal, the composition is different, which is odd. It's what we call inhomogeneous. That’s a fancy way of saying 'incompletely mixed.' The common thing about all the materials that I've looked at so far, and there's about a dozen, is that almost none of them are uniform. They're all these hodgepodge mixtures. Each individual case will be composed of a similar set of elements, but they will be inhomogeneous.

One of the materials from the so called Ubatuba event [a UAP event in Brazil], has extraordinarily altered isotope ratios of magnesium. It was interesting because another piece from the same event was analyzed in the same instrument at the same time. This is an extraordinarily sensitive instrument called a nanoSIMS - Secondary Ion Mass Spec. It had perfectly correct isotope ratios for what you would expect for magnesium found anywhere on Earth. Meanwhile, the other one was just way off. Like 30 percent off the ratios. The problem is there's no good reason humans have for altering the isotope ratios of a simple metal like magnesium. There's no different properties of the different isotopes, that anybody, at least in any of the literature that is public of the hundreds of thousands of papers published, that says this is why you would do that. Now you can do it. It's a little expensive to do, but you'd have no reason for doing it.

I mean, let’s think about what people use isotopes for today. Most of the time humans use isotopes to blow stuff up—uranium or plutonium—or to poison someone, or used as a tracer in order to kill cancer. But those are very, very specific cases. We are almost always only using radioactive isotopes. We don't ever change the isotope ratios of stable isotopes except perhaps as a tracer. What that means is that if you find a metal where the isotope ratios are changed far beyond what is normally found in nature, then that material has likely been engineered—the material is downstream of a process that caused them to be altered. Someone did it. The questions are who… and why?

So, now, let's look at what these materials are claimed to be. In almost every case, these are the leftovers of some sort of process that these objects spit out. So you go look at the cases where molten metal falls from these objects. Why would 30 pounds of a molten metal fall from a flying object?

What are the circumstances in some of these cases? For instance, in some cases the witnesses state that the observed objects appeared unstable, or in some kind of distress. Then, it spits out 'a bunch of stuff.' Now the object appears it's stable and it moves off. It looks like it fixed itself. One hypothesis would be that the material it offloads is part of the mechanism the object uses for moving around, and when things get out of whack, the object has to offload it. It just drops this stuff to the ground, kind of like the exhaust. That begs the question (again assuming the things are real at all): what are they using it for? If there's altered isotope ratios, are they using the altered isotope ratios? Are the altered ratios the result of the propulsion mechanism? Again, pure speculation: When the ratios get that far out of whack, do they have to offload because it's no longer useful in propulsion? Smarter people than me will come up with better reasons—but this is the fun of the science. The data is there… the explanation is not.

How many objects have you checked out that are not playing by our rules?

So of the 10 or 12 that I've looked at, two seem to be not playing by our rules. That doesn't mean that they're levitating, on my desk or anything, it just means that they have altered isotope ratios.

Have you ever used a super quantum interference device?

We will likely be using SQUIDs in a new device that can determine the atomic structure of anything, at a sub-angstrom resolution. There's no device in the world that can do that today, especially of an amorphous object. We can do crystals, we can do little bits of biology with what's called cryo-EM. But this device supersedes all of them. So I'm talking with the government about building that.

Are the devices and methods that you have available to you in terms of being able to analyze this material sufficient? In a perfect world, what would you want to see?

Depending on how deep you want to go, each analysis costs anywhere from $10,000 to $20,000. That tells you what the atoms are, what the isotope ratios are, crystalline quality—a lot of things that are sort of standard materials analysis. The point of doing this though is to figure out what it was used for. To do that, eventually, you do need to get down to the atomic level.

Let's say we didn't have transistors today and one of these objects dropped a big chunk of germanium doped with other elements, or, you know, these little transistors. We would not have a clue as to the function, and we would ask 'why would anyone put arrays of germanium with these strange impurities in them… what is this thing?'

Anybody who's engineering materials these days for doing any kind of advanced electronics and photonics understands that where the atoms are in the structure matters. There's a thing that's often used in biology called the structure-function relationship. Structure defines the function. Sometimes, if you can just see the structure, you can understand the function. I can look at a heart and watch a little bit of how it moves and understand its function. I can look at the tubes in your veins and say, that function is to carry blood. As we're looking at the structure of cells, when we see the structure of a protein, we can get a sense of how it's operating. So that's really what it's about. The next frontier of materials study is atomic. If you want to understand something very advanced, you better have something like this in your back pocket.

Additional reporting by Jason Koebler.

For more with Dr. Garry Nolan, watch this interview with Jesse Michels on American Alchemy.