Thanks for reading Exo! To support more explorations into geomagnetic fields, astral projections, super materials and freaky alternative worlds, consider subscribing!

Its free for like five more minutes and comes with a trendy t-shirt.

Was that too thirsty? Is this thing still on? Oh god.

In 2008, a Haitian newsroom birthed an accidentally poignant video clip. It featured a good-natured albeit slightly bewildered weatherman named Arthur who, sweeping his hands across a simplified map of the country, made the now-legendary forecast, “Pretty much everywhere it’s gonna be hot.”

Arthur had really phoned it in this time. The sheer vagueness of the update was astonishing and everyone in the room knew it. Arthur even knew it. Soon after, the entire Internet would know it. While sitting at computers across the world, an impressive portion of humanity clicked into Arthur’s moment and nodded in agreement: it’s gonna be hot.

The Caribbean weather segment and its turbo-traversal along the then freshly-laid lines of digital content distribution is a viral artifact. By today’s standards it wouldn’t stand out from your garden variety meme. But it signaled the onset of a synchronized info-world in which the data we consume and its emotional impact are increasingly shared.

Breathtaking upswings in time online, immediacy of information and unprecedented interactivity have become so universally gotten used to, we neglect to ask a crucial question: How is this coordinated state of knowingness impacting the shared ways in which we feel?

Framed a little more vastly - Are we all riding the same highs and lows of an ever-growing data-driven global consciousness?

It’s a hard question to answer. The good news is that the same technology that makes a hypothesized pan-species emotional same-state possible also offers the tools necessary to figure out whether it’s really a thing.

Let’s start by taking a look at some valiant efforts at quantifying how us is doing.

Attempts at Measurement

Feel Estate (dot com)

The same year as Arthur’s pronouncement, I got together with a friend to make a tool that could measure the world’s happiness. The idea was to put human sentiment to work to create an index of moods in regions around the world. We envisioned a graphical interface like a weather map and a proliferating set of crowd-sourced applications we could then build subsequent versions around. We called it Feel Estate (yikes).

On a Thursday evening, you might learn that the denizens of Cincinnati are having a great time and book a flight for the coming weekend. You might notice that folks are feeling particularly upbeat about Chattanooga’s high-speed broadband and decide to launch your start-up there. Or perhaps you might need to escape the vaguely abusive relationship with your current environs, absconding to somewhere a little more chill. Feel Estate was a service that helped you decide where to be.

The initiative never got off the ground. But the idea of slicing the data along a hybrid geo-vibes line remained a passing interest for years (man, Geo-Vibes would have been a good name for it). Moving on!

The Hedonometer

Also in 2008, a scientist named Peter Dodds embarked on his own journey to measure the word’s happiness/sadness.

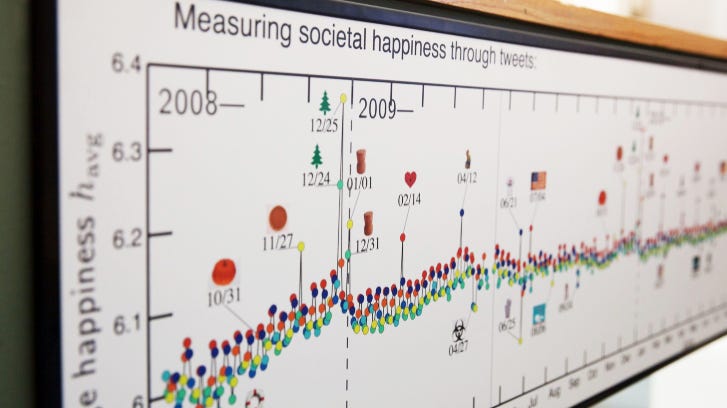

Peter called his creation the Hedonometer (better than our name, but not by much). His approach was generally in-line with what we had been thinking. He, however, had the ingenuity to tap the torrent of human sentiment pouring out of social networks. He created a list of words that were ranked on a positivity scale. With the help of Twitter’s API, he then measured their frequency of use, which in turn auto-populated a map.

Here are some snapshots of the Hedonometer in action.

Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count - LIWC

TRAGIC name. Cornell University sociologists Scott Golder and Michael Macy spent a long-ass time collecting 509 million tweets from 2.4 million users in 84 different countries. They ran it through LIWC, which reads text and counts the percentage of words that reflect different emotions, thinking styles, and social concerns.

Scott and Michael found that mood is largely tethered to time of day (as opposed to our proposed synthetic emotional root system). They concluded, “We all have basically the same biology, and the pattern we found was very robust.”

Pulse of the Nation

Northeastern University leaned into the same myopic angle as LIWC, honing in on shared mood swings throughout the day. For instance, early-morning and late-evening have the highest level of happy tweets. Here’s a pretty cool looking map of their findings:

To bolster their claim they compared this pattern as it played out in different time zones. The west coast shows happier tweets in a sequence that is consistently three hours behind the east coast.

Gallup Global Emotions Report

The global analytics behemoth Gallup took a more manual approach. In 2018, they created a snapshot of people's positive and negative daily experiences based on more than 151,000 interviews with adults in over 140 countries.

The study’s participants were asked a series of ‘Positive Experience Index’ questions like “Were you treated with respect all day yesterday?” and “Did you smile or laugh a lot yesterday?” They were also asked a series of ‘Negative Experience Index’ questions, which were equally if not more grandfatherly.

The conclusions of the report seem deeply useless - 71 percent of people worldwide said they experienced a lot of enjoyment the day before the survey; Paraguay had the highest Positive Experience Index score worldwide of 85; and Afghanistan's Positive Experience Index score dropped to a record low of 43.

The folks at Gallup did however land on a conclusion shared by many of the above reports: Inhabitants of the United States are extremely stressed out. Three of the above methodologies also reported American anxiety levels comparable with trauma. Thanks Murder Hornets!

Something Bigger Going on

Whether it’s polling individuals or Twitter-Mining the faceless masses, all the data returns two consistent findings.

On one side, as biological entities there are simply certain times of the day when we’re happier or sadder. Makes sense, work sucks, Miller time, repeat. But that only goes part of the way to explaining why we’re all vibing in the same manner at the same time.

The second trend points to shared swings in how we feel as a group beyond just the time of day. These feelings are tethered to real-world events. Their cross-section is illuminating. Let’s revisit 2019’s Hedonometer…

Evergreen holidays like Christmas, Independence Day, and Mother’s Day are largely responsible for upticks in mood. One-off current events like mass shootings, COVID, and the murder of George Floyd precipitate gigantic drops in mood. Very rarely do these two types of events switch roles.

Two more findings point to an even larger coordinated trend. Firstly, 2020’s mood did not recover like other years. In the words of Peter Dodd, the Hedonometer dude, “Negative events are tragedies. They’re shocks to the system, but the system usually recovers pretty well.” However, after the dual momentous events of 2020, the world’s happiness “took a long time to get back to roughly where it was before. That’s a signal of collective trauma.”

Secondly, the Hedonometer’s happiness level generally has been declining since 2015. The usage of words associated with sorrow and/or anger has skyrocketed. Chris Danforth, who runs the Computational Story Lab at the University of Vermont, had this to say - “The 2016 election really changed how people interacted with Twitter because of the way the president used it, and the stories he was able to tell his supporters through it really engaged people.”

So, news events are destroying our moods, the sheer amount of events is preventing us from regaining balance, and single-point access to platforms like Twitter are causing a sustained downward trend in how we feel.

The Impact

In many ways, now - quarantine, provides a perfectly controlled setting to examine the impact of a connected mood state. We’re getting really shitty headlines and we’re extremely online. Behold, the internet hive mind.

For good or for bad, we seem caught in a mood-assimilating feedback loop brought to you by a connected world™. This is in keeping with prevailing social network thinking. In the sage words of systems theorist Fritjof Capra, “The biological structure of an organism corresponds to the material infrastructure of a society, which embodies the society’s culture. As the culture evolves, so does its infrastructure - they co-evolve through continual mutual influences.”

The connected world provides a filter through which we assemble meaning out of raw data. If that digital context is largely comprised of headlines containing negative sentiment, does this mean we’re on a one way trip to bummertown? Or could another 420doggface208 save us all?

History holds some clues. This isn’t the first time we’ve become disillusioned en masse. The absurdist sensibility that has found its expression on platforms like TikTok resembles the post-World War 1 (and post-1918 pandemic) Dadaists. Their whole thing was shaking people out of an emotional inertia with unexpected visual experiences.

Our current disruptive stance has found more purpose of late. It’s even begun to chip away at the cracks of what were traditionally held to be incorruptible institutions. The technology that creates a global mood, then allows us to measure said sentiment, subsequently waking us up and bestowing upon us the tools to course-correct. Instead of an inexorable downward trend, perhaps we are just at the base of a wave that will eventually recover as it has before.

Here’s a hope - As we re-evaluate the status quo, and challenge the gatekeepers interested in keeping it, we will also rediscover our self-determination and our shared happiness. And the great Tilt-O-Whirl begins anew.

To continue twirling towards freedom,